We Built a Better Cassandra + ScyllaDB Driver for Node.js – with Rust

Lessons learned building a Rust-backed Node.js driver for ScyllaDB: bridging JS and Rust, performance pitfalls, and benchmark results

This blog post explores the story of building a new Node.js database driver as part of our Student Team Programming Project. Up ahead: troubles with bridging Rust with JavaScript, a new solution being initially a few times slower than the previous one, and a few charts!

Note: We cover the progress made until June 2025 as part of the ZPP project, which is a collaboration between ScyllaDB and University of Warsaw. Since then, the ScyllaDB Driver team adopted the project (and now it’s almost production ready).

Motivation

The database speaks one language, but users want to speak to it in multiple languages: Rust, Go, C++, Python, JavaScript, etc. This is where a driver comes in, acting as a “translator” of sorts. All the JavaScript developers of the world currently rely on the DataStax Node.js driver. It is developed with the Cassandra database in mind, but can also be used for connecting to ScyllaDB, as they use the same protocol – CQL. This driver gets the job done, but it is not designed to take full advantage of ScyllaDB’s features (e.g., shard-per-core architecture, tablets).

A solution for that is rewriting the driver and creating one that is in-house, developed and maintained by ScyllaDB developers. This is a challenging task requiring years of intensive development, with new tasks interrupting along the way. An alternative approach is writing the new driver as a wrapper around an existing one – theoretically simplifying the task (spoiler: not always) to just bridging the interfaces. This concept was proven in the making of the ScyllaDB C / C++ driver, which is an overlay over the Rust driver.

We chose the ScyllaDB Rust driver as the backend of the new JavaScript driver for a few reasons. ScyllaDB’s Rust driver is developed and maintained by ScyllaDB. That means it’s always up to date with the latest database features, bug fixes, and optimizations. And since it’s written in Rust, it offers native-level performance without sacrificing memory safety. [More background on this approach]

Development of such a solution skips the implementation of complicated database handling logic, but brings its own set of problems. We wanted our driver to be as similar as possible to the Node.js driver so anyone wanting to switch does not need to do much configuration. This was a restriction on one side. On the other side, we have limitations of the Rust driver interface. Driver implementations differ and the API for communicating with them can vary in some places. Some give a lot of responsibility to the user, requiring more effort but giving greater flexibility. Others do most of the work without allowing for much customization. Navigating these considerations is a recurring theme when choosing to write a driver as a wrapper over a different one.

Despite the challenges during development, this approach comes with some major advantages. Once the initial integration is complete, adding new ScyllaDB features becomes much easier. It’s often just a matter of implementing a few bridging functions. All the complex internal logic is handled by the Rust driver team. That means faster development, fewer bugs, and better consistency across languages. On top of that, Rust is significantly faster than Node.js. So if we keep the overhead from the bridging layer low, the resulting driver can actually outperform existing solutions in terms of raw speed.

The environment: Napi vs Napi-Rs vs Neon

With the goal of creating a driver that uses ScyllaDB Rust Driver underneath, we needed to decide how we would be communicating between languages. There are two main options when it comes to communicating between JavaScript and other languages:

- Use a Node API (NAPI for short) – an API built directly into the NodeJS engine, or

- Interface the program through the V8 JavaScript engine.

While we could use one of those communication methods directly, they are dedicated for C / C++, which would mean writing a lot of unsafe code.

Luckily, other options exist: NAPI-RS and Neon. Those libraries handle all the unsafe code required for using the C / C++ APIs and expose (mostly safe) Rust interfaces. The first option uses NAPI exclusively under the hood, while the Neon option uses both of those interfaces.

After some consideration, we decided to use NAPI-RS over Neon. Here are the things we considered when deciding which library to use:

– Library approach — In NAPI-RS, the library handles the serialization of data into the expected Rust types. This lets us take full advantage of Rust’s static typing and any related optimizations. With Neon, on the other hand, we have to manually parse values into the correct types.

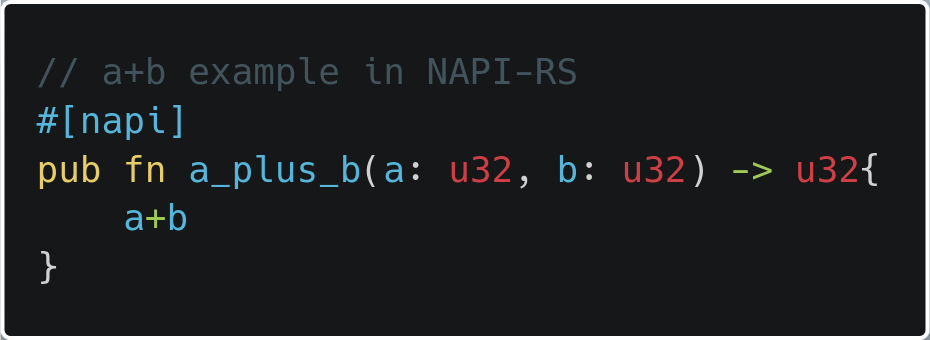

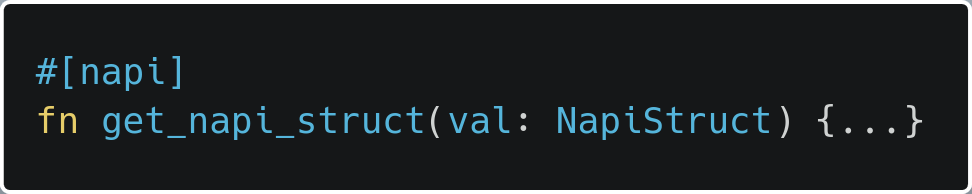

With NAPI-RS, writing a simple function is as easy as adding a #[napi] tag:

Simple a+b example

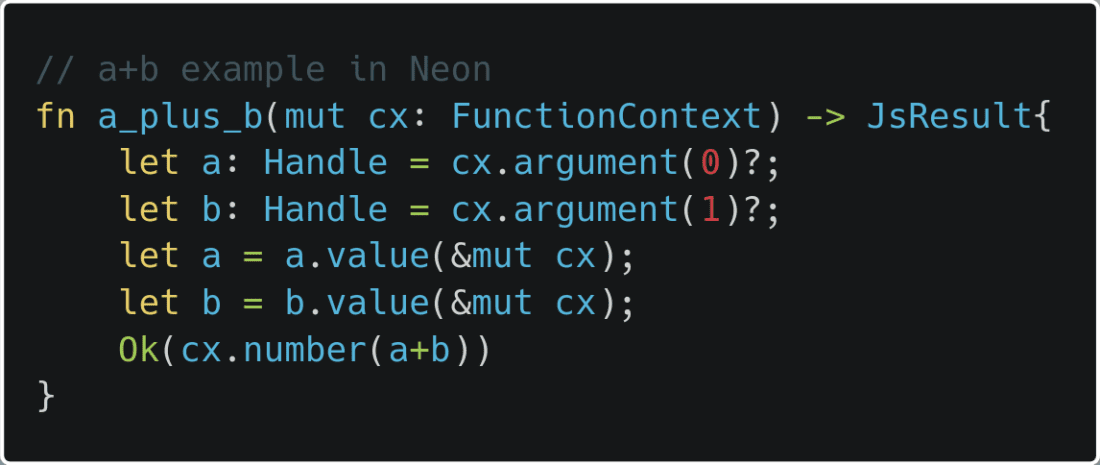

And in Neon, we need to manually handle JavaScript context:

A+b example in Neon

– Simplicity of use — As a result of the serialization model, NAPI-RS leads to cleaner and shorter code. When we were implementing some code samples for the performance comparison, we had serious trouble implementing code in Neon just for a simple example. Based on that experience, we assumed similar issues would likely occur in the future.

– Performance — We made some simple tests comparing the performance of library function calls and sending data between languages. While both options were visibly slower than pure JavaScript code, the NAPI-RS version had better performance. Since driver efficiency is a critical requirement, this was an important factor in our decision. You can read more about the benchmarks in our thesis.

– Documentation — Although the documentation for both tools is far from perfect, NAPI-RS’s documentation is slightly more complete and easier to navigate.

Current state and capabilities

Note: This represents the state as of May 2025. More features have been introduced since then. See the project readme for a brief overview of current and planned features.

The driver supports regular statements (both select and insert) and batch statements. It supports all CQL types, including encoding from almost all allowed JS types. We support prepared statements (when the driver knows the expected types based on the prepared statement), and we support unprepared statements (where users can either provide type hints, or the driver guesses expected value types).

Error handling is one of the few major functions that behaves differently than the DataStax driver. Since the Rust driver throws different types of errors depending on the situation, it’s nearly impossible to map all of them reliably. To avoid losing valuable information, we pass through the original Rust errors as is. However, when errors are generated by our own logic in the wrapper, we try to keep them consistent with the old driver’s error types.

In the DataStax driver, you needed to explicitly call shutdown() to close the database connection. This generated some problems: when the connection variable was dropped, the connection sometimes wouldn’t stop gracefully, even keeping the program running in some situations. We decided to switch this approach, so that the connection is automatically closed when the variable keeping the client is dropped. For now, it’s still possible to call shutdown on the client.

Note: We are still discussing the right approach to handling a shutdown. As a result, the behavior described here may change in the future.

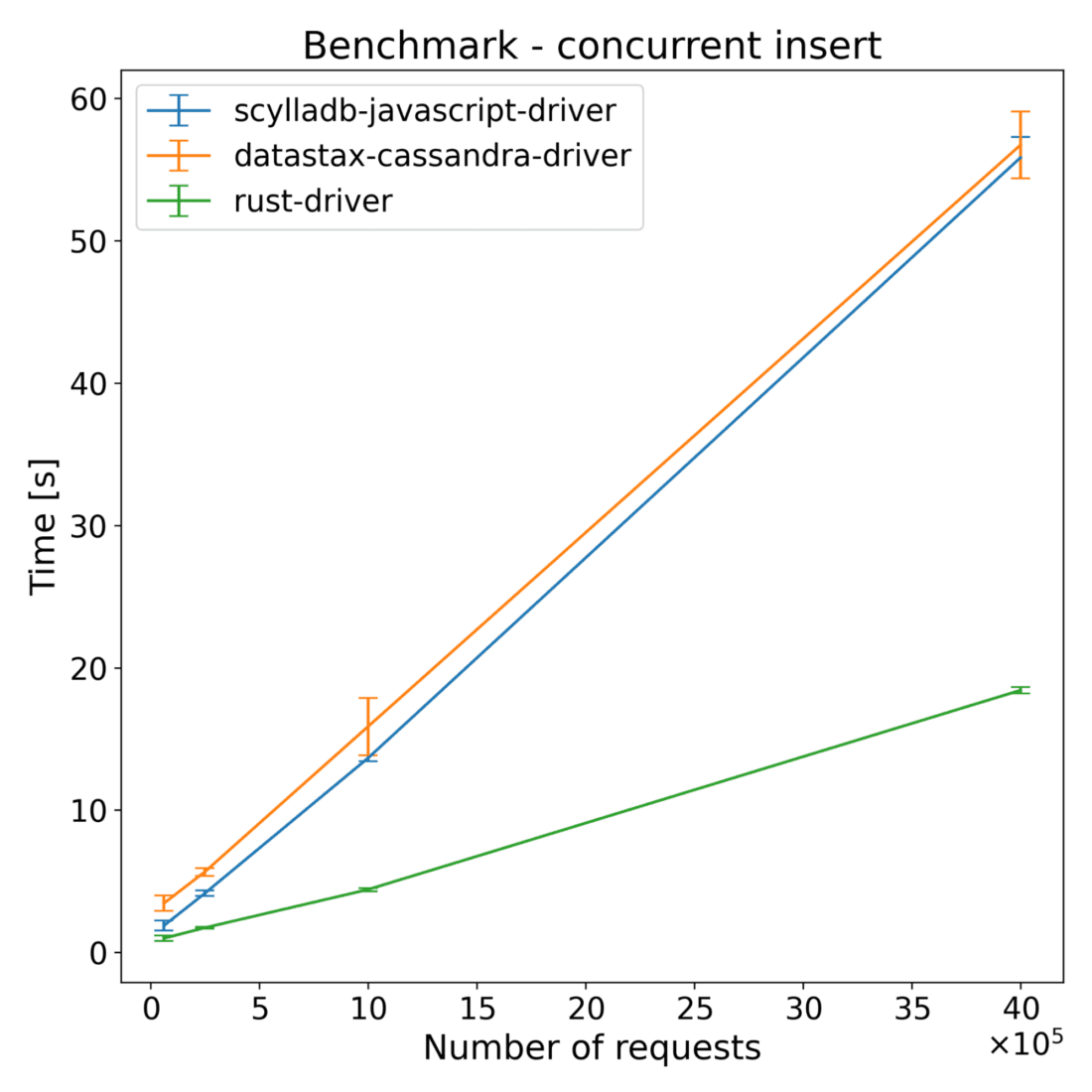

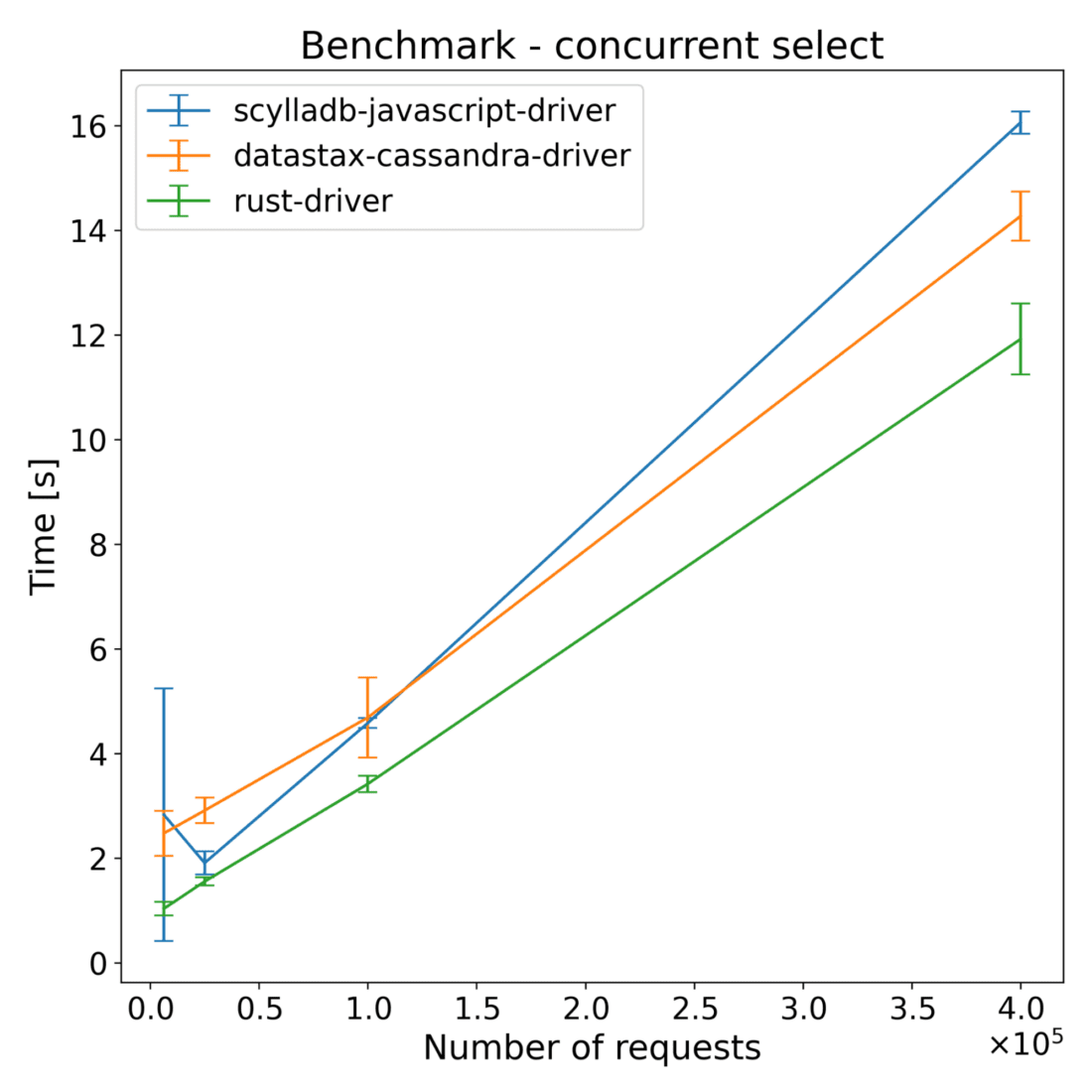

Concurrent execution

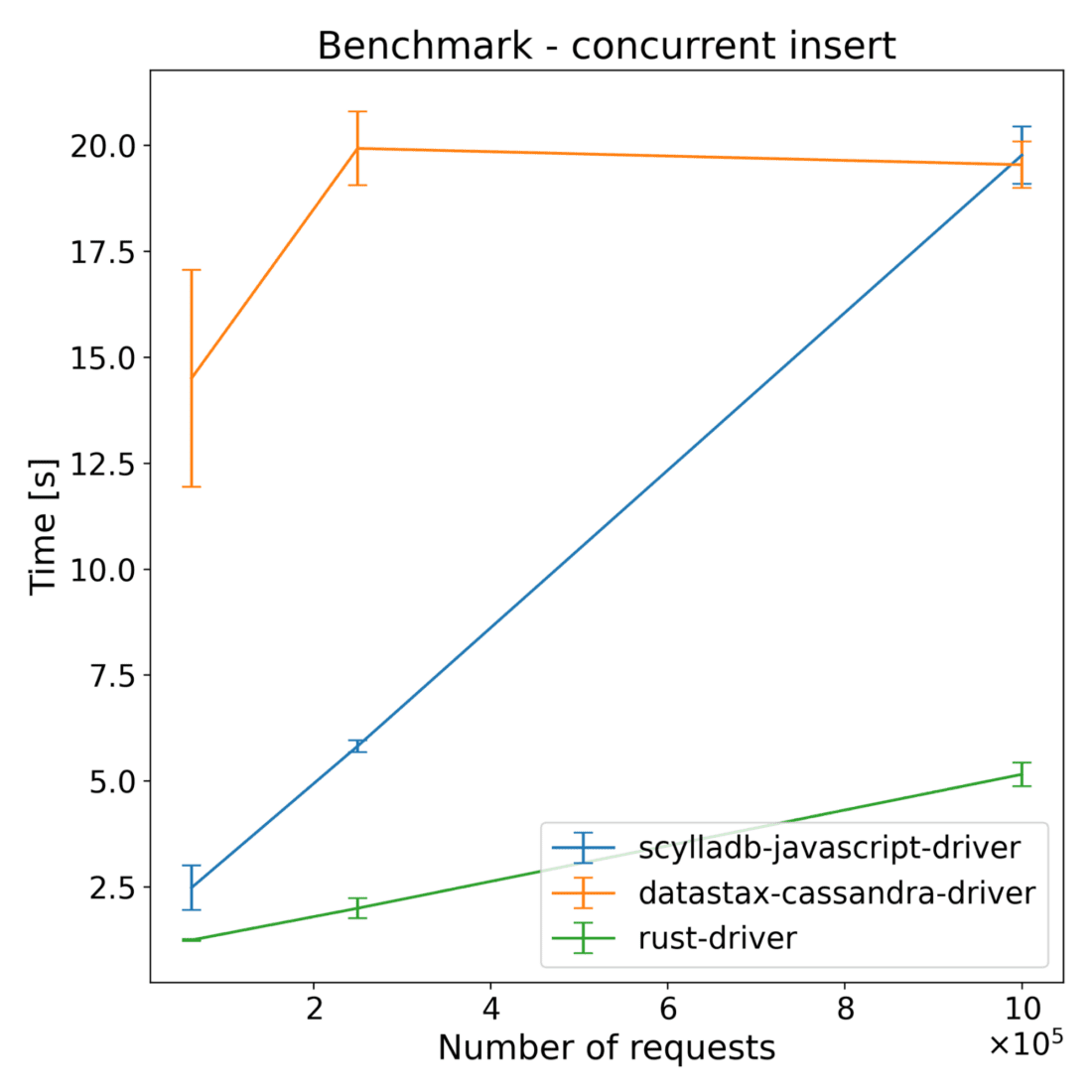

The driver has a dedicated endpoint for executing multiple queries concurrently. While this endpoint gives you less control over individual requests — for example, all statements must be prepared and you can’t set different options per statement — these constraints allow us to optimize performance. In fact, this approach is already more efficient than manually executing queries in parallel (around 35% faster in our internal testing), and we have additional optimization ideas planned for future implementation.

Paging

The Rust and DataStax drivers both have built-in support for paging, a CQL feature that allows splitting results of large queries into multiple chunks (pages). Interestingly, although the DataStax driver has multiple endpoints for paging, it doesn’t allow execution of unpaged queries. Our driver supports the paging endpoints (for now, one of those endpoints is still missing) and we also added the ability to execute unpaged queries in case someone ever needs that.

With the current paging API, you have several options for retrieving paged results:

- Automatic iteration: You can iterate over all rows in the result set, and the driver will automatically request the next pages as needed.

- Manual paging: You can manually request the next page of results when you’re ready, giving you more control over the paging process.

- Page state transfer: You can extract the current page state and use it to fetch the next page from a different instance of the driver. This is especially useful in scenarios like stateless web servers, where requests may be handled by different server instances.

Prepared statements cache

Whenever executing multiple instances of the same statement, it’s recommended to use prepared statements. In ScyllaDB Rust Driver, by default, it’s the user’s responsibility to keep track of the already prepared statements to avoid preparing them multiple times (and, as a result, increasing both the network usage and execution times). In the DataStax driver, it was the driver’s responsibility to avoid preparing the same query multiple times. In the new driver, we use Rust’s Driver Caching Session for (most) of the statement caching.

Optimizations

One of the initial goals for the project was to have a driver that is faster than the DataStax driver. While using NAPI-RS added some overhead, we hoped the performance of the Rust driver would help us achieve this goal.

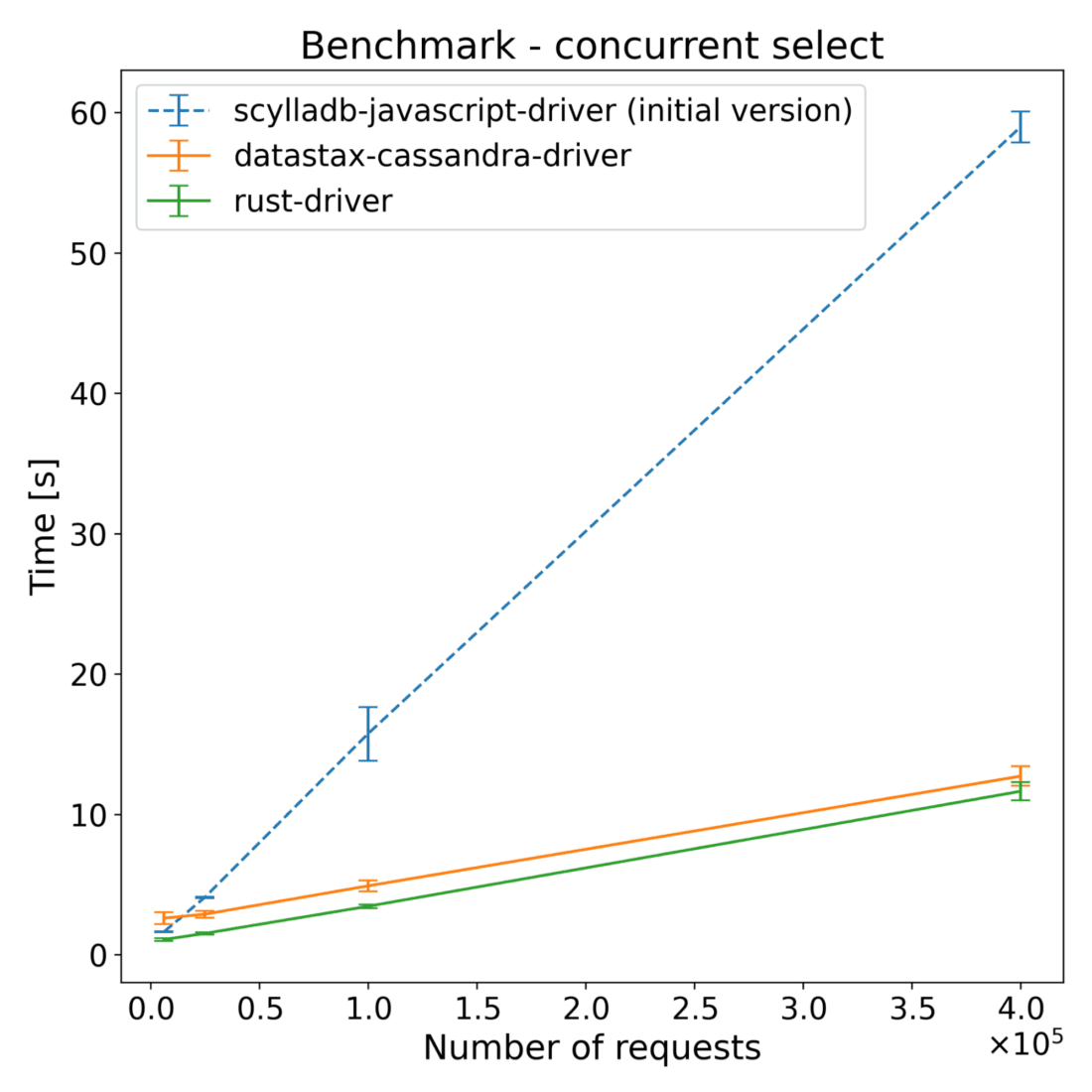

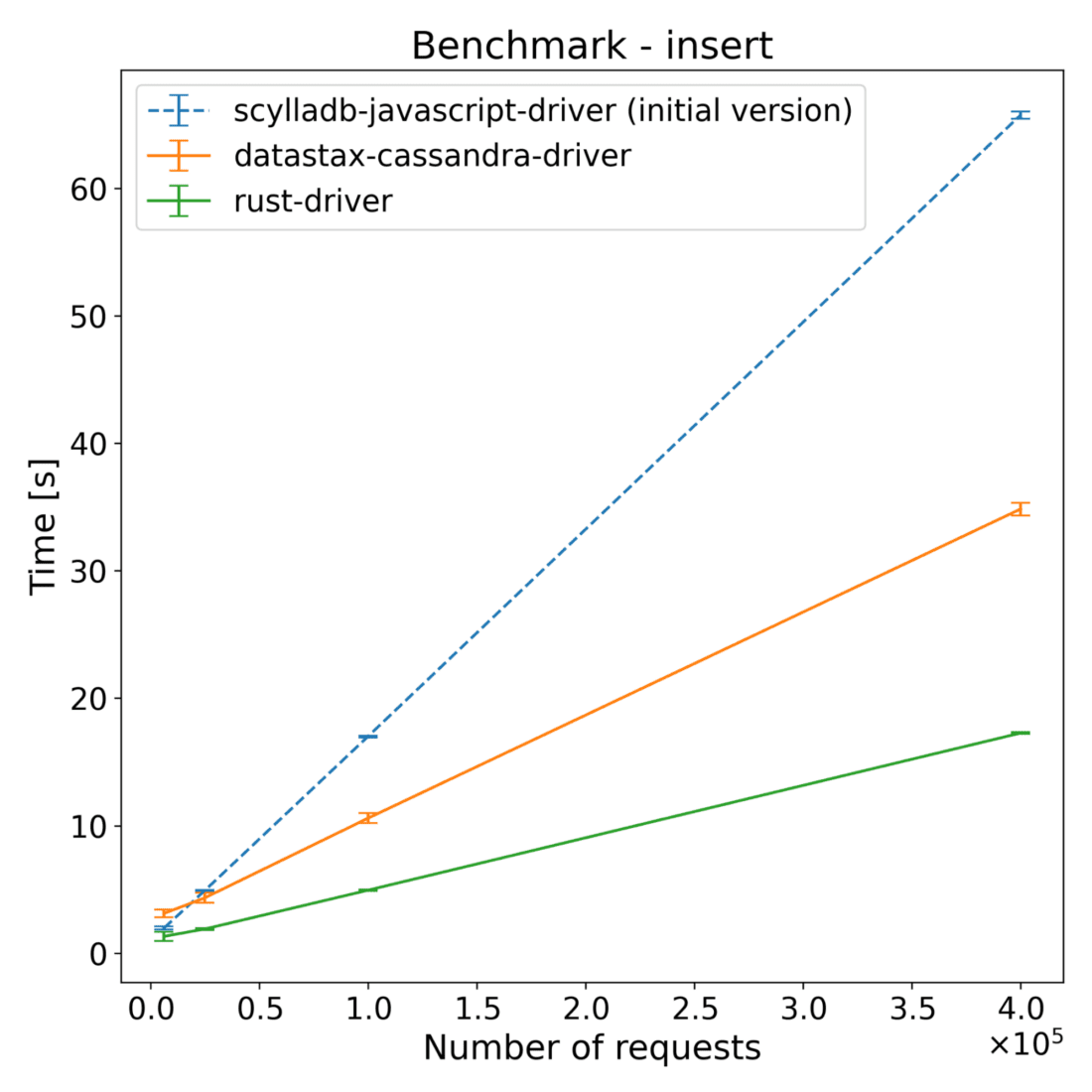

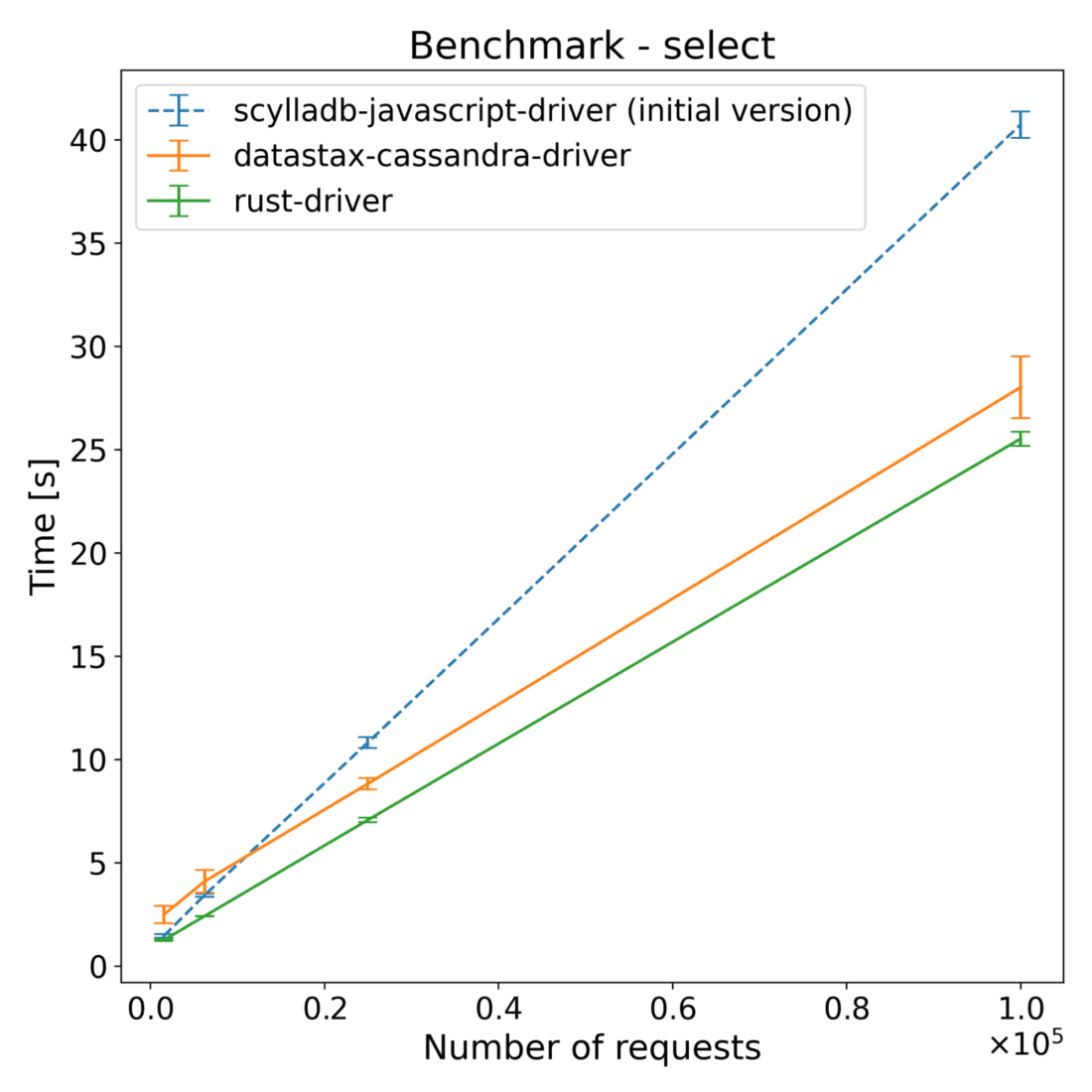

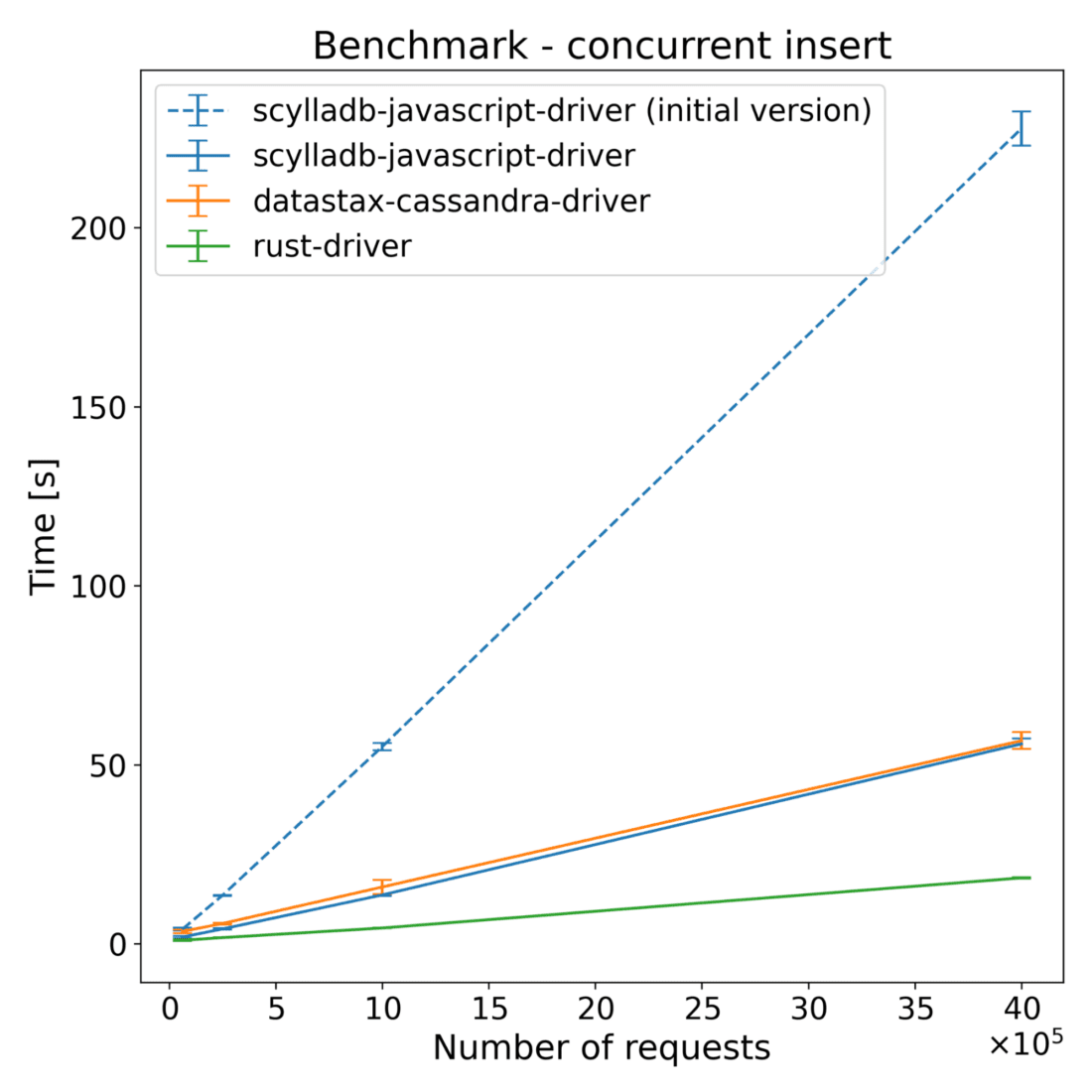

With the initial implementation, we didn’t put much focus on efficient usage of the NAPI-RS layer. When we first benchmarked the new driver, it turned out to be way slower compared to both the DataStax JavaScript driver and the ScyllaDB Rust driver…

| Operations | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 4.08 | 3.53 | 1.04 |

| 250000 | 13.50 | 5.81 | 1.73 |

| 1000000 | 55.05 | 15.37 | 4.61 |

| 4000000 | 227.69 | 66.95 | 18.43 |

| Operations | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.63 | 2.61 | 1.08 |

| 250000 | 4.09 | 2.89 | 1.52 |

| 1000000 | 15.74 | 4.90 | 3.45 |

| 4000000 | 58.96 | 12.72 | 11.64 |

| Operations | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.63 | 2.61 | 1.08 |

| 250000 | 4.09 | 2.89 | 1.52 |

| 1000000 | 15.74 | 4.90 | 3.45 |

| 4000000 | 58.96 | 12.72 | 11.64 |

| Operations | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.96 | 3.11 | 1.31 |

| 250000 | 4.90 | 4.33 | 1.89 |

| 1000000 | 16.99 | 10.58 | 4.93 |

| 4000000 | 65.74 | 31.83 | 17.26 |

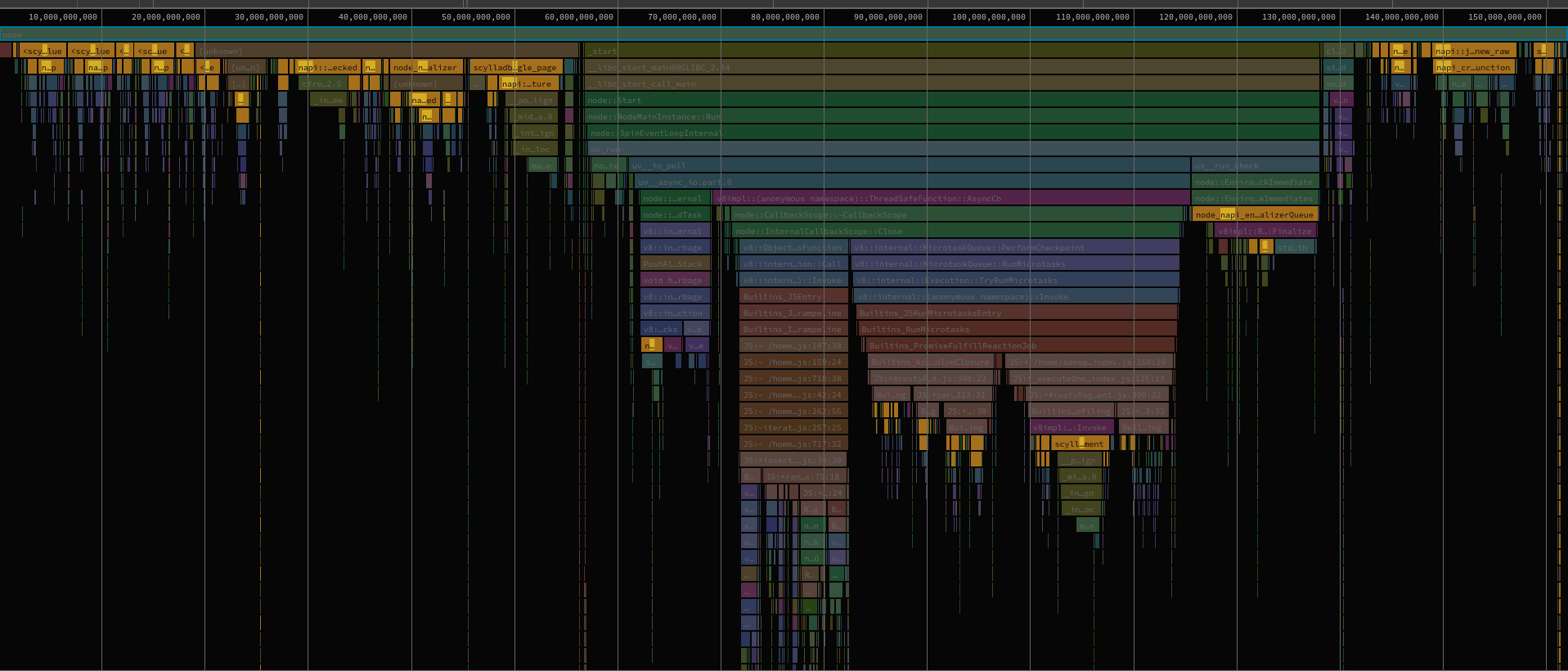

Those results were a bit of a surprise, as we didn’t fully anticipate how much overhead NAPI-RS would introduce. It turns out that using JavaScript Objects introduced way higher overhead compared to other built-in types, or Buffers. You can see on the following flame graph how much time was spent executing NAPI functions (yellow-orange highlight), which are related to sending objects between languages.

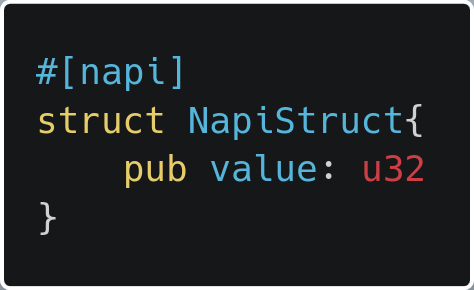

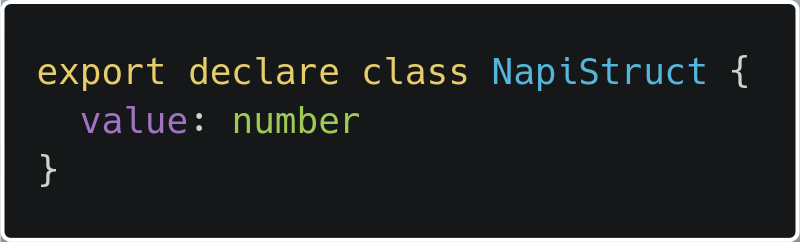

Creating objects with NAPI-RS is as simple as adding the #[napi] tag to the struct we want to expose to the NodeJS part of the code. This approach also allows us to create methods on those objects. Unfortunately, given its overhead, we needed to switch the approach – especially in the most used parts of the driver, like parsing parameters, results, or other parts of executing queries.

We can create a napi object like this:

Which is converted to the following JavaScript class:

We can use this struct between JavaScript and Rust.

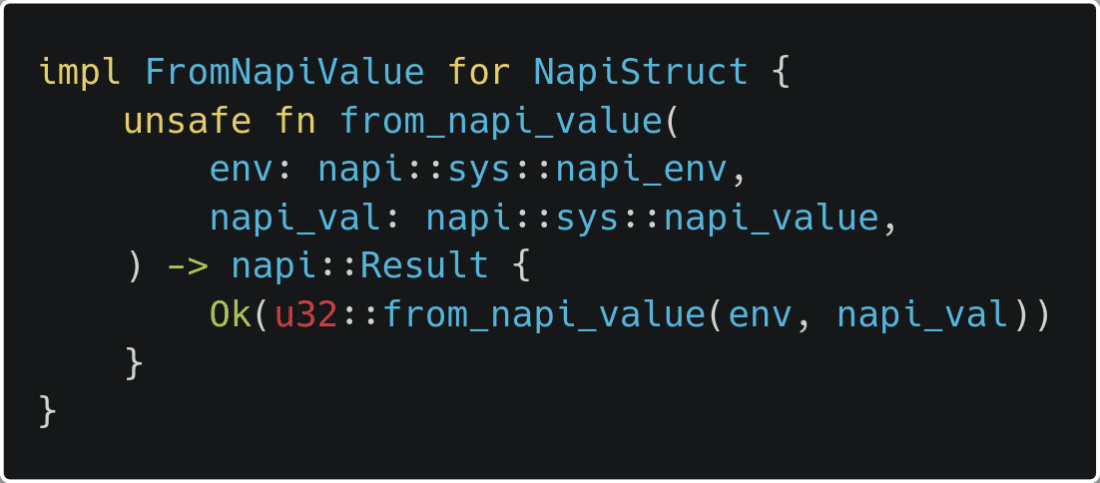

When accepting values as arguments to Rust functions exposed in NAPI-RS, we can either accept values of the types that implement the FromNapiValue trait, or accept references to values of types that are exposed to NAPI (these implement the default FromNapiReference trait).

We can do it like this:

Then, when we call the following Rust function

we can just pass a number in the JavaScript code.

FromNapiValue is implemented for built-in types like numbers or strings, and the FromNapiReference trait is created automatically when using the #[napi] tag on a Rust struct. Compared to that, we need to manually implement FromNapiValue for custom structs. However, this approach allows us to receive those objects in functions exposed to NodeJS, without the need for creating Objects – and thus significantly improves performance. We used this mostly to improve the performance of passing query parameters to the Rust side of the driver.

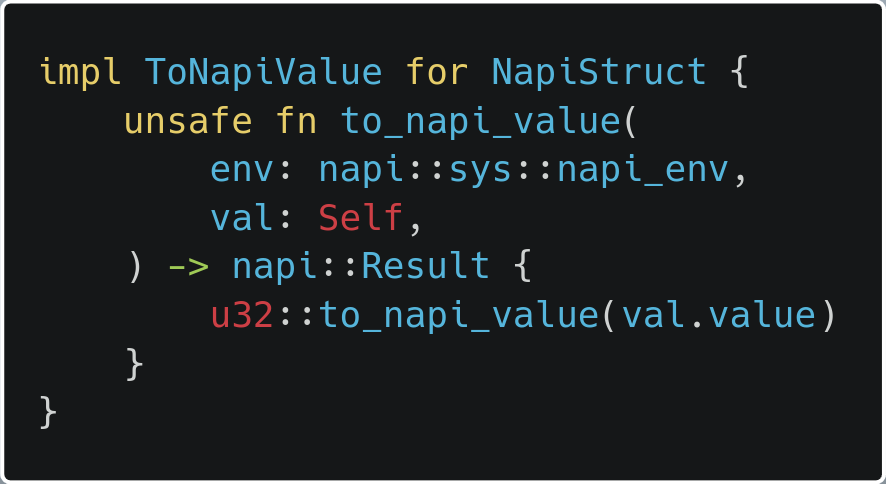

When it comes to returning values from Rust code, a type must have a ToNapiValue trait implemented. Similarly, this trait is already implemented for built-in types, and is auto generated with macros when adding the #[napi] tag to the object. And this auto generated implementation was causing most of our performance problems. Luckily, we can also implement our own ToNapiValue trait. If we return a raw value and create an object directly in the JavaScript part of the code, we can avoid almost all of the negative performance impacts that come from the default implementation of ToNapiValue.

This will return just the number instead of the whole struct.

An example of such places in the code was UUID. This type is used for providing the UUID retrieved as part of any query, and can also be used for inserts. In the initial implementation, we had a UUID wrapper: an object created in the Rust part of the code, that had a default ToNapiValue implementation, that was handling all the logic for the UUID. When we changed the approach to returning just a raw buffer representing the UUID and handling all the logic on the JavaScript side, we shaved off about 20% of the CPU time we were using in the select benchmarks at that point in time.

Note: Since completing the initial project, we’ve introduced additional changes to how serialization and deserialization works. This means the current state may be different from what we describe here. A new round of benchmarking is in progress; stay tuned for those results.

Benchmarks

In the previous section, we showed you some early benchmarks. Let’s talk a bit more about how we tested and what we tested.

All benchmarks presented here were run on a single machine – the database was run in a Docker container and the driver benchmarks were run without any virtualization or containerization. The machine was running on AMD Ryzen™ 7 PRO 7840U with 32GB RAM, with the database itself limited to 8GB of RAM in total.

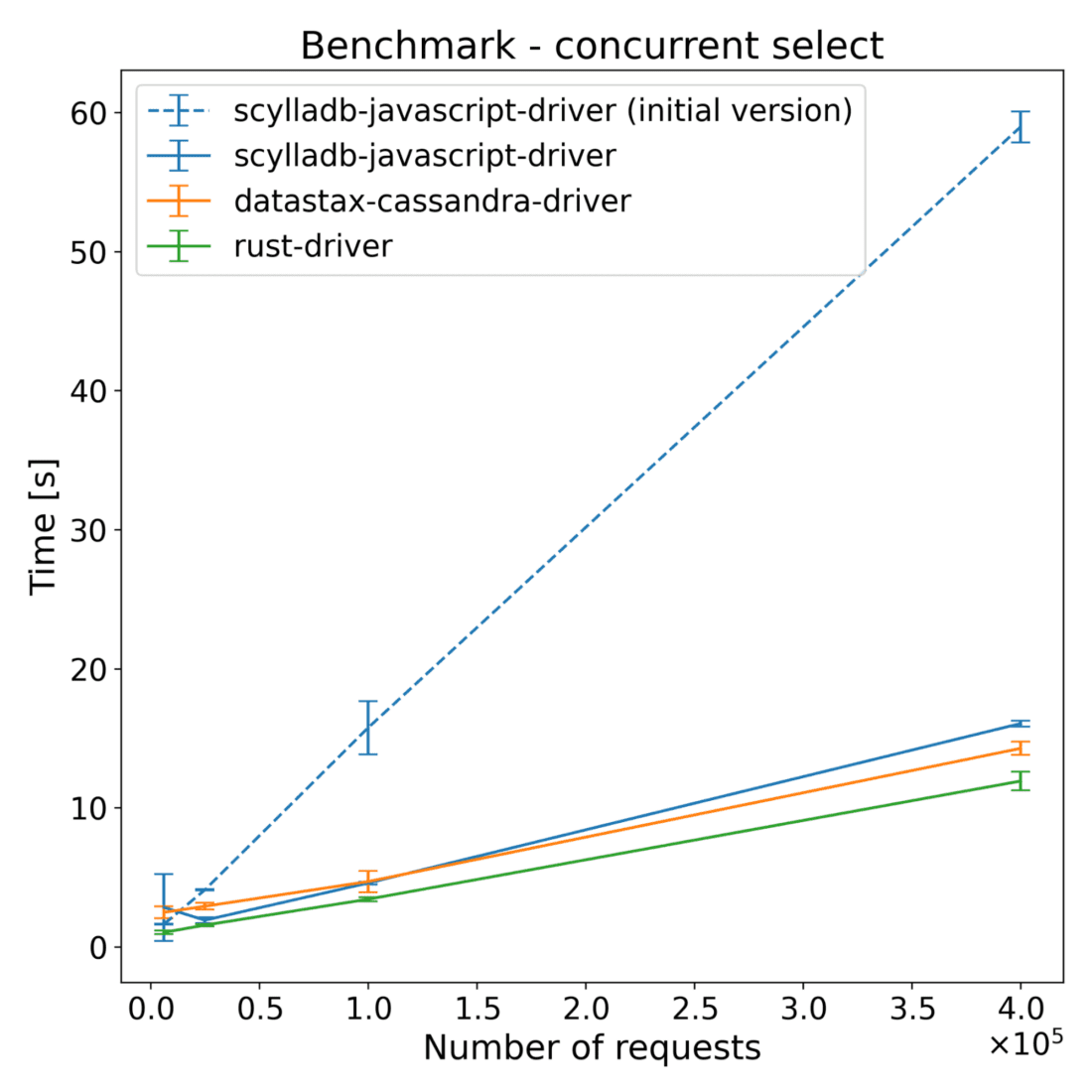

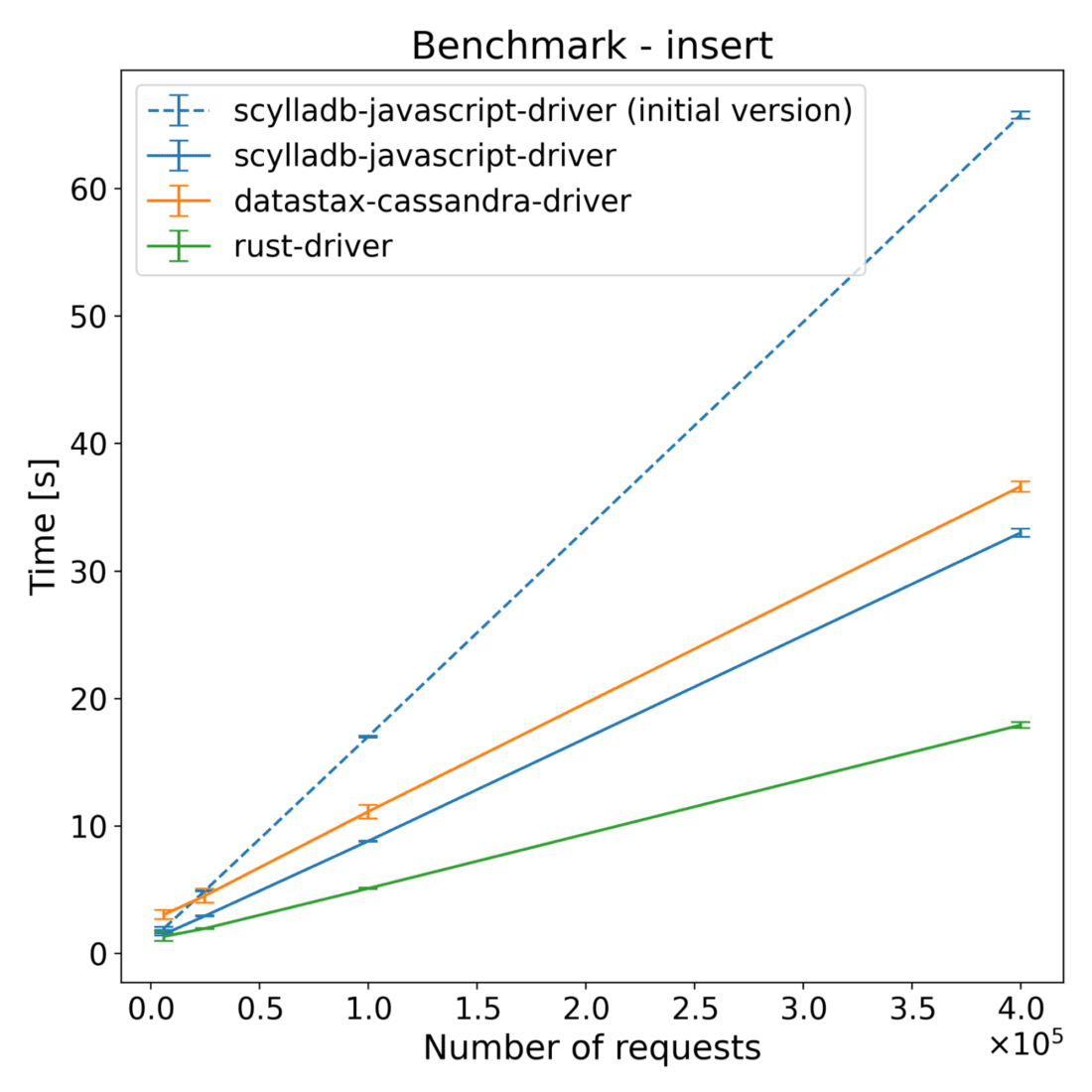

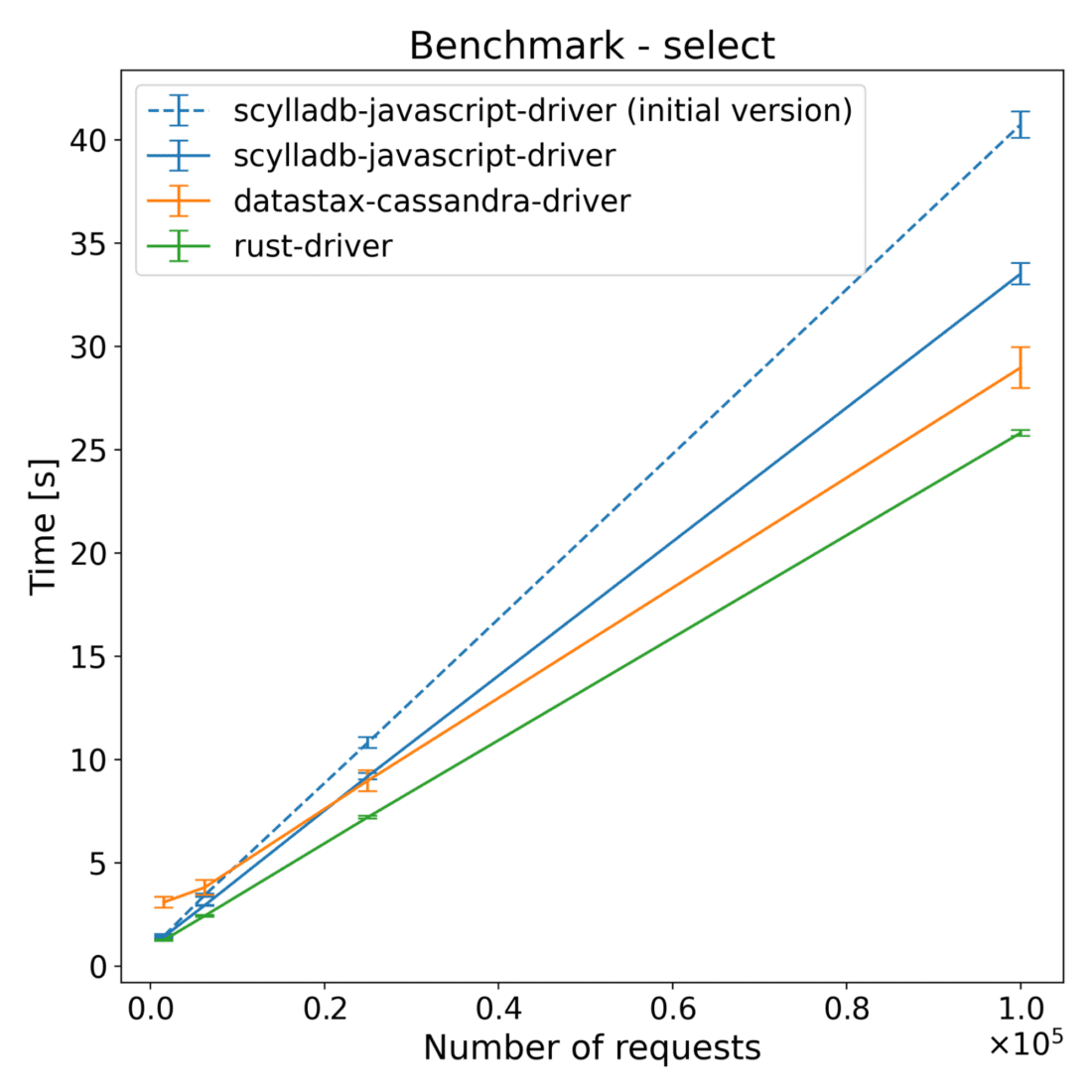

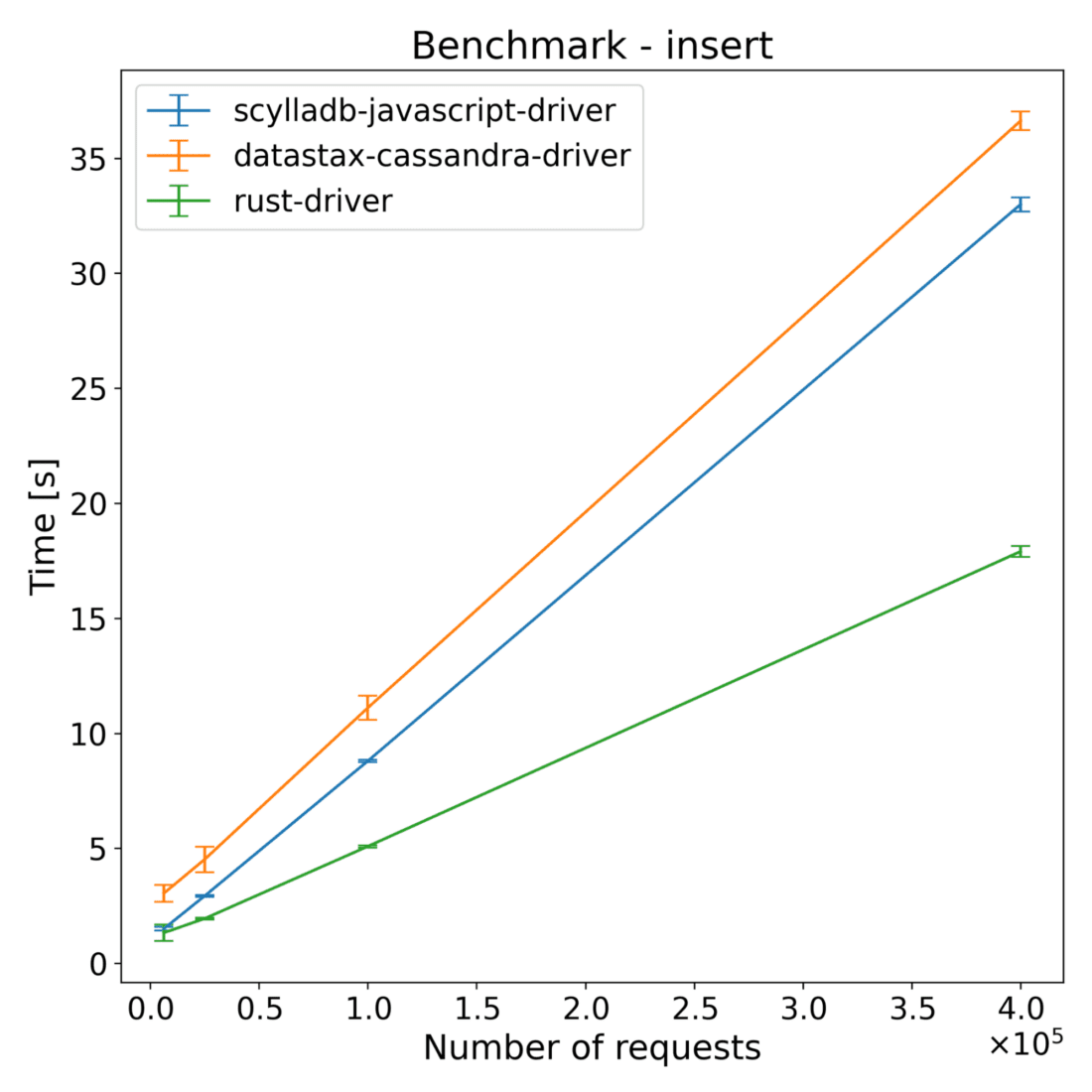

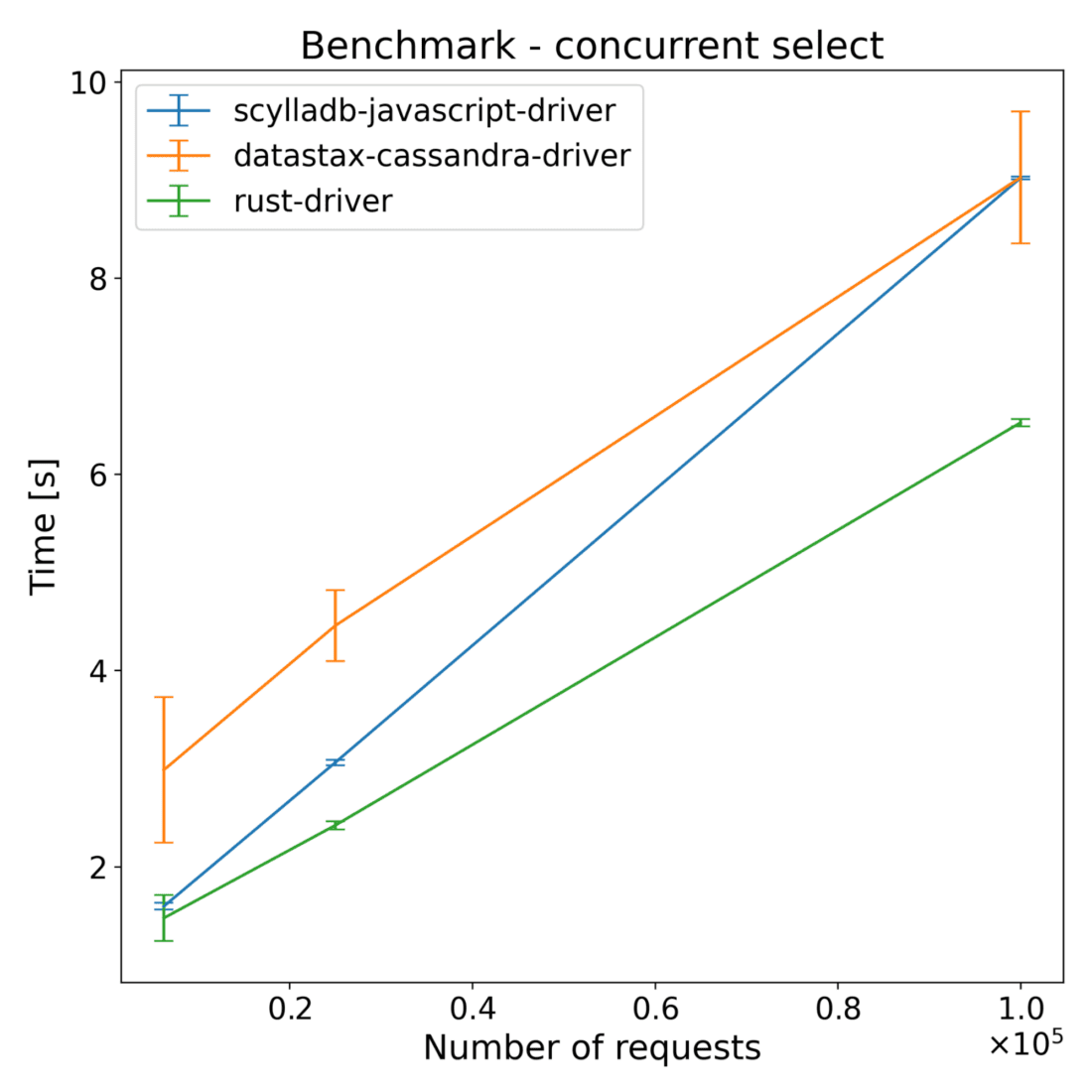

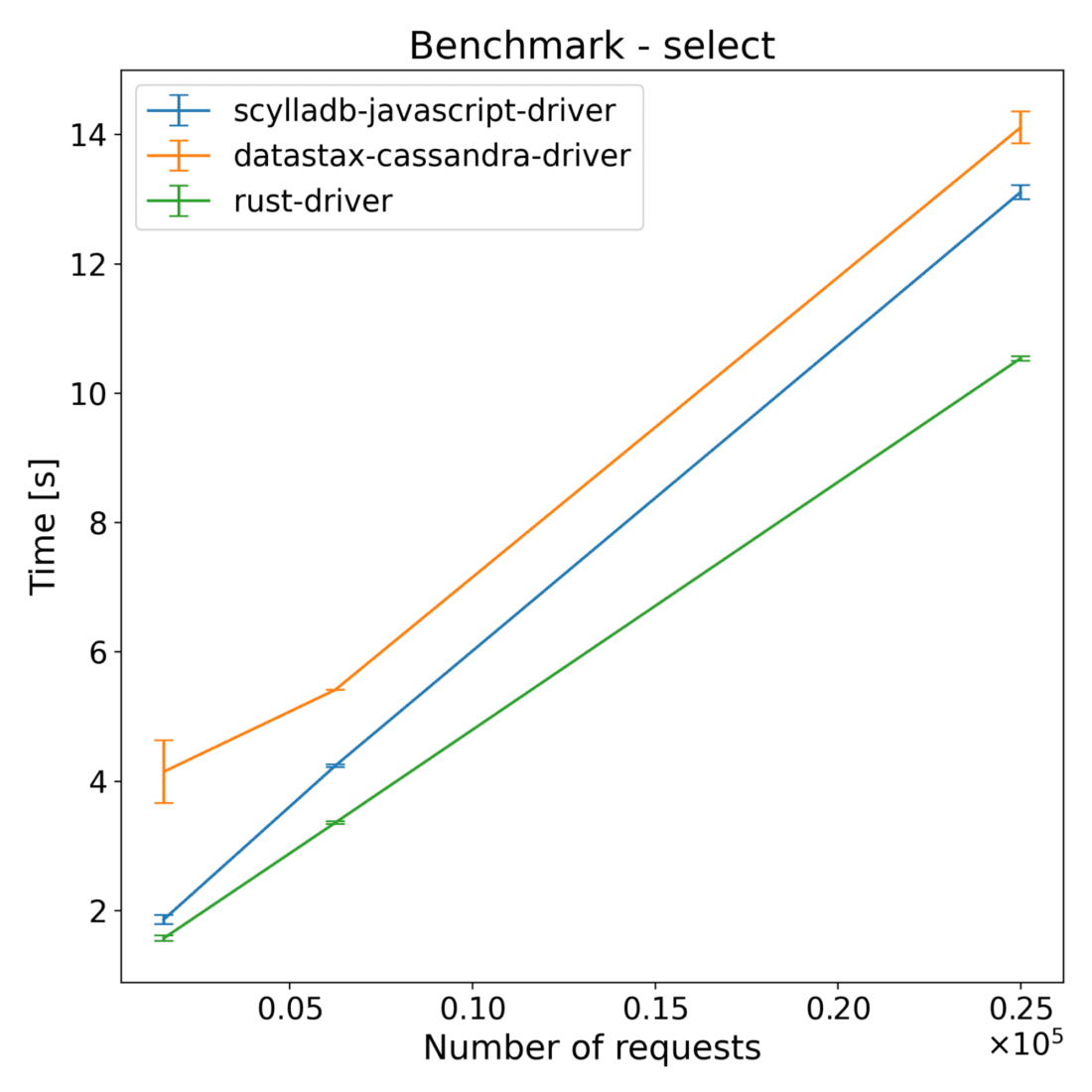

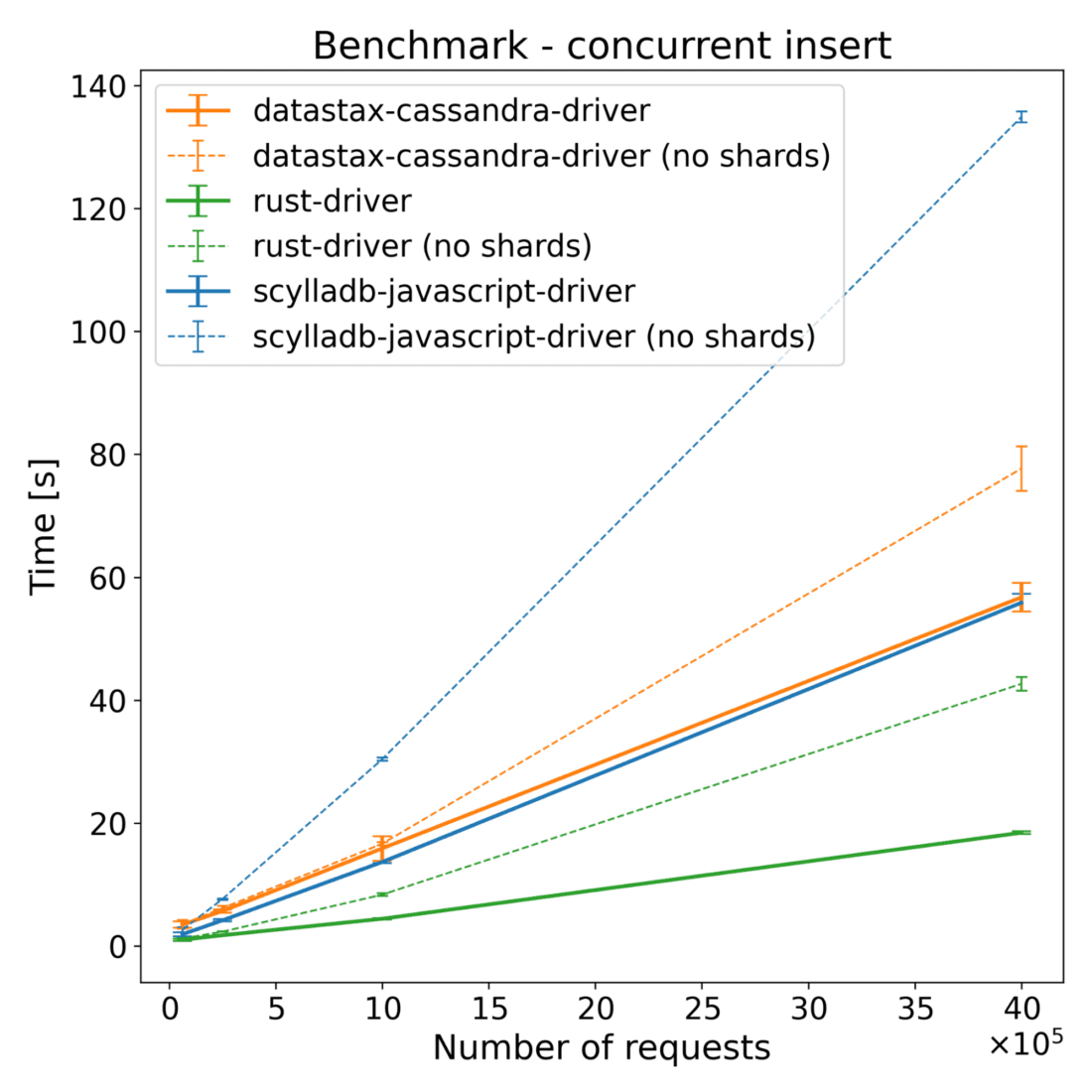

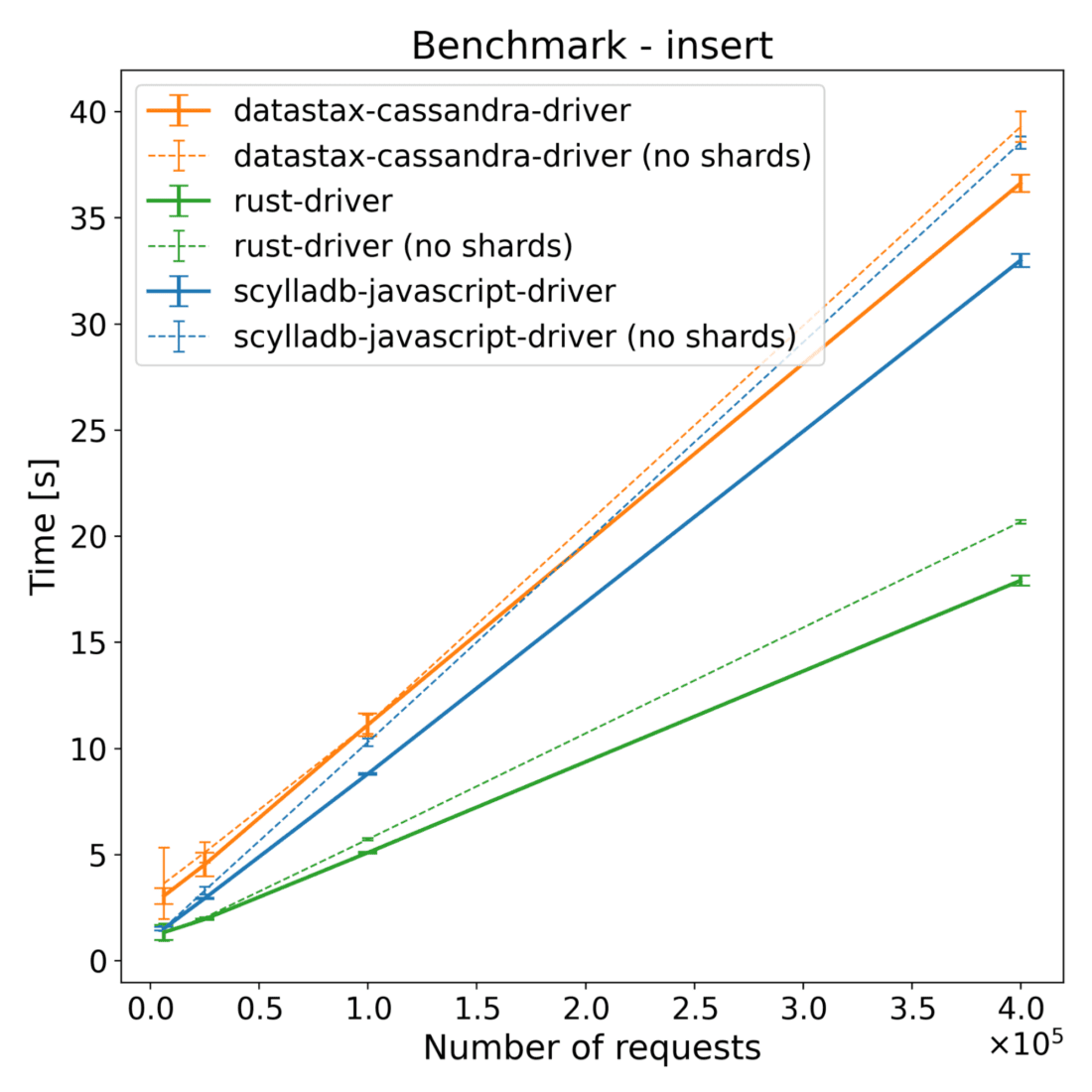

We tested the driver both with ScyllaDB and Cassandra (latest stable versions as of the time of testing – May 2025). Both of those databases were run in a three node configuration, with 2 shards per node in the case of ScyllaDB. With this information on the benchmarks, let’s see the effect all the optimizations we added had on the driver performance when tested with ScyllaDB:

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.89 | 3.45 | 0.99 | 4.08 |

| 250000 | 4.15 | 5.66 | 1.73 | 13.50 |

| 1000000 | 13.65 | 15.86 | 4.41 | 55.05 |

| 4000000 | 55.85 | 56.73 | 18.42 | 227.69 |

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 2.83 | 2.48 | 1.04 | 1.63 |

| 250000 | 1.91 | 2.91 | 1.56 | 4.09 |

| 1000000 | 4.58 | 4.69 | 3.42 | 15.74 |

| 4000000 | 16.05 | 14.27 | 11.92 | 58.96 |

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.50 | 3.04 | 1.33 | 1.96 |

| 250000 | 2.93 | 4.52 | 1.94 | 4.90 |

| 1000000 | 8.79 | 11.11 | 5.08 | 16.99 |

| 4000000 | 32.99 | 36.62 | 17.90 | 65.74 |

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] | scylladb-javascript-driver (initial version) [s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.42 | 3.09 | 1.25 | 1.45 |

| 250000 | 2.94 | 3.81 | 2.43 | 3.43 |

| 1000000 | 9.19 | 8.98 | 7.21 | 10.82 |

| 4000000 | 33.51 | 28.97 | 25.81 | 40.74 |

And here are the same benchmarks, without the initial driver version.

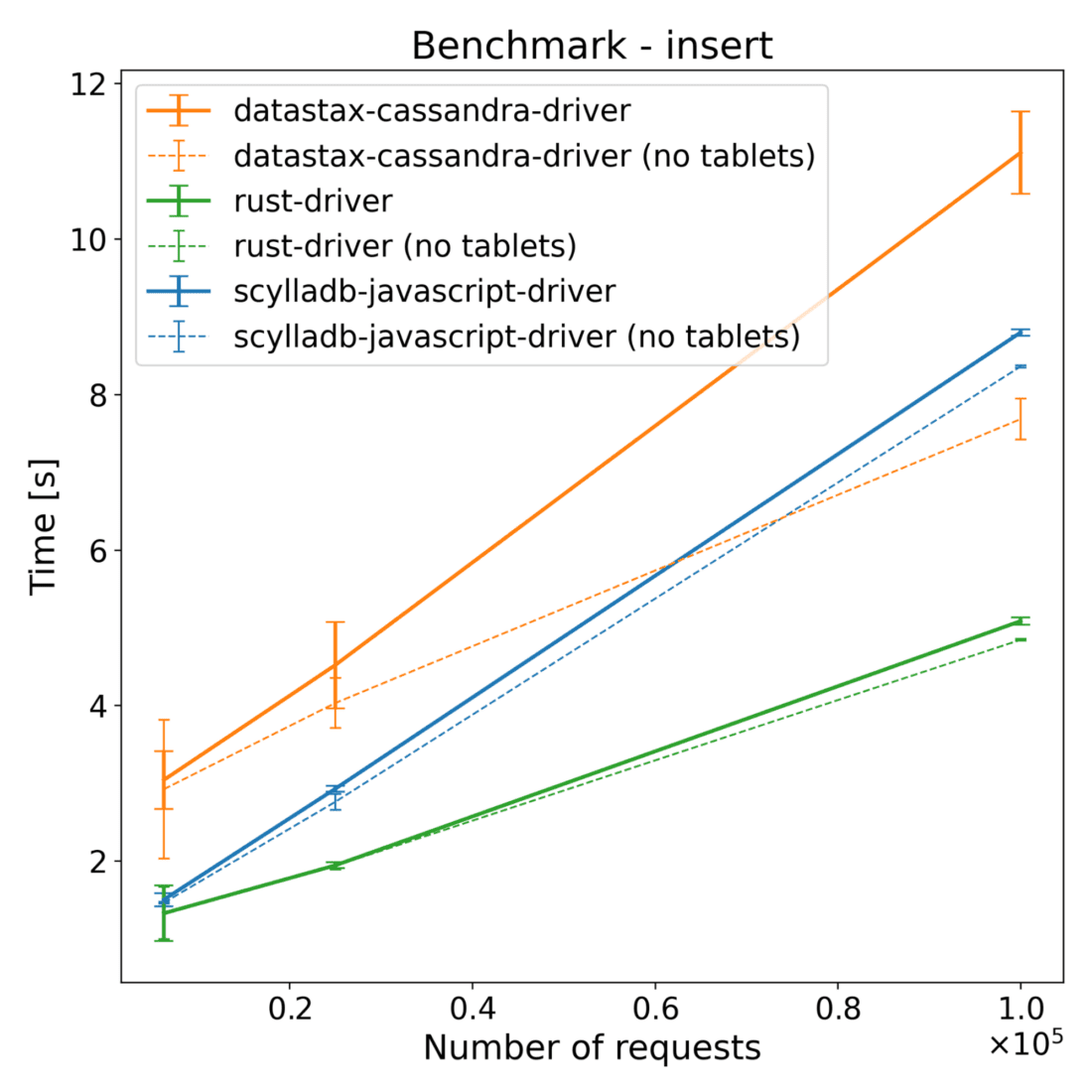

Here are the results of running the benchmark on Cassandra.

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 2.48 | 14.50 | 1.25 |

| 250000 | 5.82 | 19.93 | 2.00 |

| 1000000 | 19.77 | 19.54 | 5.16 |

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.60 | 2.99 | 1.48 |

| 250000 | 3.06 | 4.46 | 2.42 |

| 1000000 | 9.02 | 9.03 | 6.53 |

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 2.32 | 4.03 | 2.11 |

| 250000 | 5.45 | 6.53 | 4.01 |

| 1000000 | 18.77 | 16.20 | 13.21 |

| Operations | Scylladb-javascript-driver [s] | Datastax-cassandra-driver [s] | Rust-driver [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 62500 | 1.86 | 4.15 | 1.57 |

| 250000 | 4.24 | 5.41 | 3.36 |

| 1000000 | 13.11 | 14.11 | 10.54 |

The test results across both ScyllaDB and Cassandra show that the new driver has slightly better performance on the insert benchmarks. For select benchmarks, it starts ahead and the performance advantage decreases with time. Despite a series of optimizations, the majority of the CPU time still comes from NAPI communication and thread synchronization (according to internal flamegraph testing). There is still some room for improvement, which we’re going to explore.

Since running those benchmarks, we introduced changes that improve the performance of the driver. With those improvements performance of select benchmarks is much closer to the speed of the DataStax driver. Again…please stay tuned for another blog post with updated results.

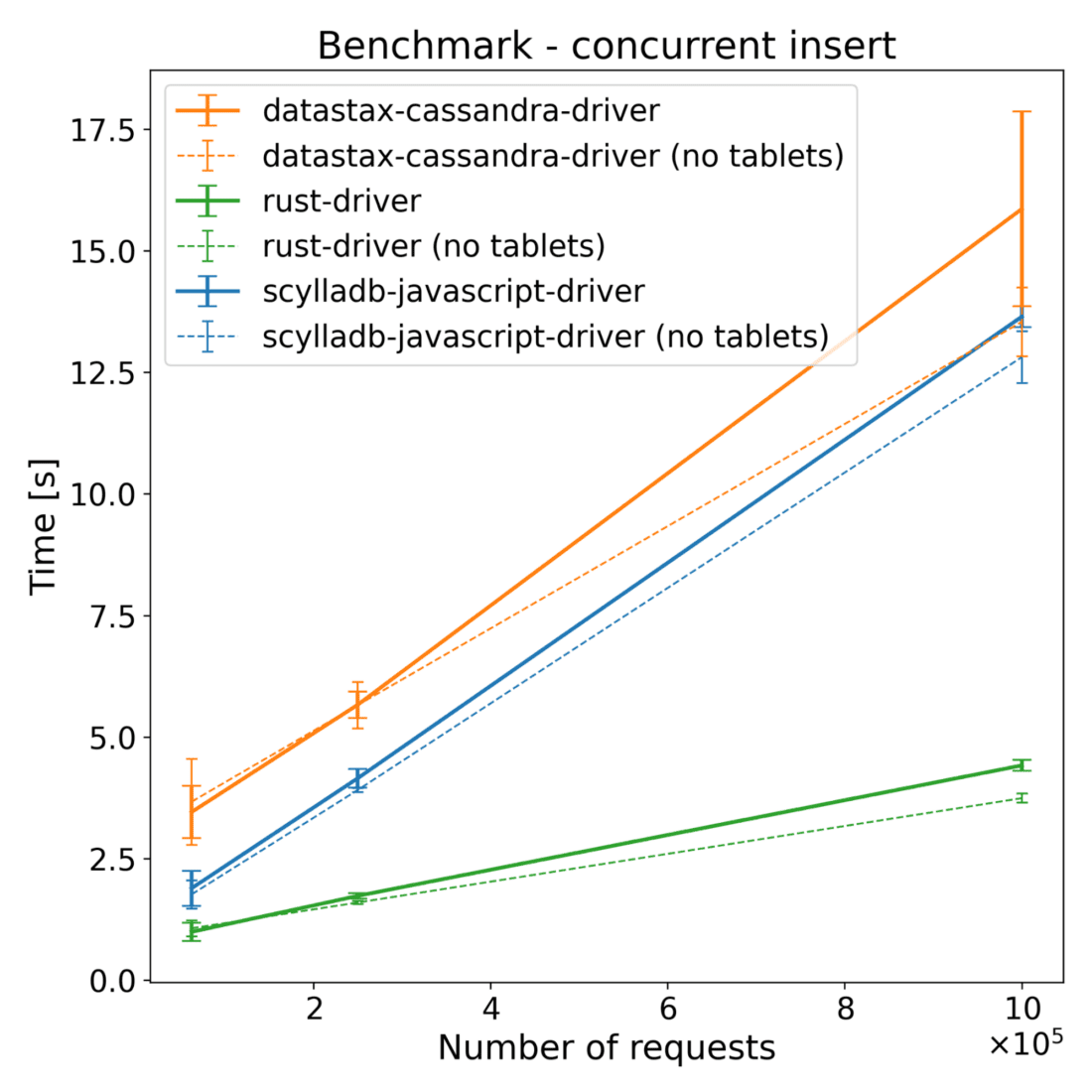

Shards and tablets

Since the DataStax driver lacked tablet and shard support, we were curious if our new shard-aware and tablet-aware drivers provided a measurable performance gain with shards and tablets.

| Operations | ScyllaDB JS Driver [s] | DataStax Driver [s] | Rust Driver [s] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shard-Aware | No Shards | Shard-Aware | No Shards | Shard-Aware | No Shards | |

| 62,500 | 1.89 | 2.61 | 3.45 | 3.51 | 0.99 | 1.20 |

| 250,000 | 4.15 | 7.61 | 5.66 | 6.14 | 1.73 | 2.30 |

| 1,000,000 | 13.65 | 30.36 | 15.86 | 16.62 | 4.41 | 8.33 |

| 4,000,000 | 55.85 | 134.90 | 56.73 | 77.68 | 18.42 | 42.64 |

| Operations | ScyllaDB JS Driver [s] | DataStax Driver [s] | Rust Driver [s] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shard-Aware | No Shards | Shard-Aware | No Shards | Shard-Aware | No Shards | |

| 62,500 | 1.50 | 1.52 | 3.04 | 3.63 | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| 250,000 | 2.93 | 3.29 | 4.52 | 5.09 | 1.94 | 2.02 |

| 1,000,000 | 8.79 | 10.29 | 11.11 | 11.13 | 5.08 | 5.71 |

| 4,000,000 | 32.99 | 38.53 | 36.62 | 39.28 | 17.90 | 20.67 |

In insert benchmarks, there are noticeable changes across all drivers when having more than one shard. The Rust driver improved by around 36%, the new driver improved by around 46%, and the DataStax driver improved by only around 10% when compared to the single sharded version. While sharding provides some performance benefits for the DataStax driver, which is not shard aware, the new driver benefits significantly more — achieving performance improvements comparable to the Rust driver. This shows that it’s not only introducing more shards that provide an improvement in this case; a major part of the performance improvement is indeed shard-awareness.

| Operations | ScyllaDB JS Driver [s] | DataStax Driver [s] | Rust Driver [s] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Tablets | Standard | No Tablets | Standard | No Tablets | Standard | |

| 62,500 | 1.76 | 1.89 | 3.67 | 3.45 | 1.06 | 0.99 |

| 250,000 | 3.91 | 4.15 | 5.65 | 5.66 | 1.59 | 1.73 |

| 1,000,000 | 12.81 | 13.65 | 13.54 | 15.86 | 3.74 | 4.41 |

| Operations | ScyllaDB JS Driver [s] | DataStax Driver [s] | Rust Driver [s] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Tablets | Standard | No Tablets | Standard | No Tablets | Standard | |

| 62,500 | 1.46 | 1.50 | 2.92 | 3.04 | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| 250,000 | 2.76 | 2.93 | 4.03 | 4.52 | 1.94 | 1.94 |

| 1,000,000 | 8.36 | 8.79 | 7.68 | 11.11 | 4.84 | 5.08 |

When it comes to tablets, the new driver and the Rust driver see only minimal changes to the performance, while the performance of the DataStax driver drops significantly. This behavior is expected. The DataStax driver is not aware of the tablets. As a result, it is unable to communicate directly with the node that will store the data – and that increases the time spent waiting on network communication. Interesting things happen, however, when we look at the network traffic:

| WHAT | TOTAL | CQL | TCP | Total Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New driver 3 node all | 412,764 | 112,318 | 300,446 | ∼ 43.7 MB |

| New driver 3 node | driver ↔ database | 409,678 | 112,318 | 297,360 | – |

| New driver 3 node | node ↔ node | 3,086 | 0 | 3,086 | – |

| DataStax driver 3 node all | 268,037 | 45,052 | 222,985 | ∼ 81.2 MB |

| DataStax driver 3 node | driver ↔ database | 90,978 | 45,052 | 45,926 | – |

| DataStax driver 3 node | node ↔ node | 177,059 | 0 | 177,059 | – |

This table shows the number of packets sent during the concurrent insert benchmark on three-node ScyllaDB with 2 shards per node. Those results were obtained with RF = 1. While running the database with such a replication factor is not production-suitable, we chose it to better visualize the results. When looking at those numbers, we can draw the following conclusions:

- The new driver has a different coalescing mechanism. It has a shorter wait time, which means it sends more messages to the database and achieves lower latencies.

- The new driver knows which node(s) will store the data. This reduces internal traffic between database nodes and lets the database serve more traffic with the same resources.

Future plans

The goal of this project was to create a working prototype, which we managed to successfully achieve. It’s available at https://github.com/scylladb/nodejs-rs-driver, but it’s considered experimental at this point. Expect it to change considerably, with ongoing work and refactors. Some of the features that were present in DataStax driver, and are expected for the driver to be considered deployment-ready, are not yet implemented. The Drivers team is actively working to add those features. If you’re interested in this project and would like to contribute, here’s the project’s GitHub repository.